Interview with Tim Ingold

Interview with Tim Ingold

What are your first memories of the ASA, and how has it changed since then?

For me, it all goes back to the Decennial Conference of the ASA, held in Oxford in 1973. I was at that time a lowly research student, recently returned from fieldwork among Skolt Sámi people in the far northeast of Finland, and in the initial throes of writing up. Such inferior beings were not formally eligible for admission to the Association’s conferences, but my supervisor, John Barnes, had somehow managed to sneak me in, and even to have me present a paper. It was a terrifying, and in some ways humiliating experience. I knew nobody. One afternoon there was a reception in one of the colleges, in which every arriving guest was greeted by the illustrious and alcoholic E. E. Evans-Pritchard. I duly presented myself, and gave my name. ‘Who?’, he boomed, for all to hear. Later, however, at dinner, I found myself seated next to Mary Douglas. Understanding my predicament, she went around the room, patiently putting a name to every face. It was a kindness I would never forget.

The Association is unrecognisable from what it was then, and a good thing too! It has a much larger and more diverse membership, researchers early in their careers are in the lead, and doctoral students are welcome participants in conferences. And of course, in its mission to protect and promote the discipline of Social Anthropology, the Association is having to deal with the quite different challenges of today, above all in the universities, where anthropologists find themselves having to compete for scarce funds and precarious employment in a ruthless and often hostile academic environment. But at the same time, the ASA’s remit has narrowed from the days when Social Anthropology could pride itself as a uniquely British school. Since then, other countries have established their own professional associations. Above all, in the wake of the establishment of the European Association of Social Anthropologists, the ASA has had to settle for a more modest role as one national organisation among many. This, too, has been all to the good.

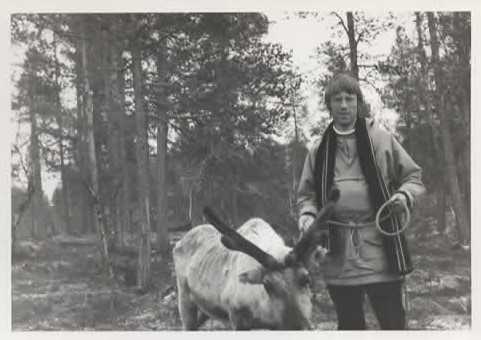

Summer 1971, me (aged 22) and Enoch the reindeer, during fieldwork in Finnish Lapland.

Summer 1971, me (aged 22) and Enoch the reindeer, during fieldwork in Finnish Lapland.

What about the ASA conferences? Have they changed too?

They have indeed, very much. Apart from being more open these days, and welcoming to participants at every career stage, I think there are two big differences between then and now. The first reflects changes in the discipline. There was a sense, both in the early conferences and in the monographs that emerged from them, of laying the foundations for what then was still a comparatively new field of study. Thus, each event and monograph could cover what we would now regard as an entire subfield: religion, history, language, kinship and marriage, medicine, law, the body, work, ecology, and so on. But once the foundational work was done, conferences turned increasingly to filling in the details. Their topics became narrower and more specialised, while monographs began to acquire sometimes elaborate subtitles. One downside of this specialisation was that people would only go if the topic happened to match their interests, making it harder for the conferences to serve their primary purpose as an annual get-together. The second difference between then and now was a reaction to this. It lay in the emergence of the broad-themed, multi-panel conference format that we are so familiar with today. This is great for inclusivity, and for giving everyone an opportunity to display their wares. But with a potpourri of panels, packed with brief and often disparate contributions, it is not so good for the collective task of delineating a theme and moving it forward. Perhaps a solution is to alternate between the two formats, so as to get the best of both worlds. Yet it is equally possible, as we think twice about long-haul travel, and learn new techniques of digital participation, that entirely new formats will emerge.

What’s your view of social anthropology as a discipline? Does it have a future?

I have always thought of myself, in the first place, as an anthropologist rather than a social anthropologist. As a student in the late 1960s, I took up anthropology in the hope that it would help bridge the ever-widening gap between the humanities and the natural sciences, but in a way that stays close to the realities of experience. That’s still why I do it now. Yet the attempt to assimilate anthropology to social science in the positivistic mould, as a ‘natural science of society’, manifestly failed. Instead, social anthropology joined up with cultural anthropology on the side of the humanities, drifting ever further from those fields of anthropology that aligned themselves with the biological sciences. Anthropology ended up split down the middle by the very division I thought it existed to overcome! Pitching my own tent in ecological anthropology, I’ve been trying my best to bring the two sides, social and biological, together again. But it’s been a frustrating business. I sometimes think that biological anthropologists, especially those of an evolutionist persuasion, are their own worst enemies, adhering doggedly to a reductionist paradigm that refuses any dialogue not conducted in its own terms. Meanwhile, most social anthropologists blithely assume they have the whole of anthropology to themselves, carrying on as if other fields simply didn’t exist.

I have to confess that nowadays, whenever I thumb through recent issues of mainstream social anthropology journals, I feel a stranger to what I find there. Perhaps it is simply that the social anthropological mainstream has drifted in one way and I’ve drifted in another. But much of the problem, to my mind, comes down to anthropology’s current and, I hope, passing obsession with ethnography. I think this has unduly narrowed our horizons, making us overwhelmingly inward-facing. Ethnographers study people in order to write about their lives. But to do anthropology, in my view, is to study with others; not to make studies of them. It is to draw on their wisdom and experience in a speculative inquiry into what the conditions and possibilities of life might be. With the world on a knife-edge, this is wisdom and experience we cannot afford to ignore. We have to learn from it, not simply treat it as data for analysis. This means taking it seriously. No other discipline, apart from anthropology, is prepared to do this. That’s why anthropology matters, not just to anthropologists but to everyone. We can only make the future together.

What are you writing on at the moment?

Just now, I have reached something of a watershed. I officially retired in September 2018, and since then I’ve been hard at work wrapping up the results of a couple of projects. One was Knowing From the Inside (KFI), a 5-year project funded by the European Research Council. The idea of the project was for anthropology to join forces with art, architecture and design in trialling an experimental mode of inquiry into the conditions of sustainable living, based on the premise that knowledge grows from the crucible of our practical and observational engagements with the world around us. The other, funded by the British Academy, was an exploration into the archaeological anthropology of materials, entitled Solid Fluids in the Anthropocene. Co-directed with Cris Simonetti, this involved a series of exchanges with anthropological and archaeological colleagues and students in the UK and Chile. An eponymous edited volume from the KFI project is due out in March this year, while a collection of papers from ‘Solid Fluids’ has just come out as a special issue of the journal Theory, Culture and Society. Besides these, I have put together a collection of personal reflections, mostly written in response to artworks and other provocations, which was published in 2020 under the title Correspondences, and November 2021 saw the publication of a new collection of essays, Imagining for Real, along with new editions of my previous collections The Perception of the Environment (2000) and Being Alive (2011). Together, these latter three books form a trilogy, rounding off three decades of work.

So what’s next? I’m hoping to return to the field in Finnish Lapland. Back in 1979-80 I carried out a year’s fieldwork in the community of Salla, in eastern Lapland, to follow up on my earlier, doctoral fieldwork with the Skolt Sámi. Salla’s predominantly Finnish population of farmers, forestry workers and reindeer herdsmen had shared the experience, in the 1940s, of wartime displacement and resettlement, but the community had also suffered severe depopulation in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the wake of Finland’s rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. My aim had been to compare the Sámi and Finnish experience, but other priorities at the time meant that beyond a handful of articles, I never properly did so. I now plan to pick up from where I left off in 1980. I have more field and archival work to do, before writing up a full-length study. It should keep me busy for the next few years.

Autumn 2016, me again, 45 years later, during an artists’ walk on the island of Skye.

Autumn 2016, me again, 45 years later, during an artists’ walk on the island of Skye.

And what am I doing on the ASA Committee?

I joined the Committee in March 2019, so I will soon have been on it for three years. I don’t have any specific role, but I hope that I can contribute some useful experience.